Journal of Humanitarian Medicine - vol. XI - n. 2 - April/June 2011

HEALTH NEEDS OF MIGRATING AND DISPLACED POPULATIONS

Brian D. GushuIak, MD, Migration Health ConsuItants, Inc., Singapore

Regent, International Association for Humanitarian Medicine

SUMMARY

International migrants make up a large and important part of the world’s population. As the world continues to become ever more globalized and integrated, migration and the health aspects of the global migrant community will assume greater prominence. Migrants are a diverse and dynamic population and some migrant cohorts such as refugees, asylum seekers, and migrant workers have serious and specific health needs related to their condition. Other migrant populations carry with them specific health and medical characteristics that may have national, regional, and in some cases international health and public health implications. Many individuals move through aspects of the population mobility continuum and while their administrative immigration status may change, their health parameters more closely reflect their origin, migrant history, and experience than their designation. Appreciating the scope and nature of the health needs of migrants in that context, and developing and delivering programmes to provide health services to these populations, can be facilitated through an organized approach based on the process of migratory mobility itself.

Introduction

Migration and the international movement of individuals and communities have always been an integral component of human existence. However, the increasing forces of globalization support and sustain the mobility of human populations in a manner that presents differences from several historical migratory population flows. The size and characteristics of these migrant populations have important implications both nationally and globally in the economic, social, political, security and health sectors. In terms of health, migration and population mobility present challenges to the provision and delivery of health services for millions of individuals and the processes of migration itself can create specific health needs that differ markedly from those of the host population. Meeting those needs effectively requires an understanding of the implications and nature of the relationships between migration and health. The terms “refugee” and “displaced person” are fundamentally administrative designations reflecting status and migrant category. In actuality refugees and displaced populations are components of the broader group of migrants and other mobile populations. Depending on location and situation, groups of refugees and the displaced may become immigrants, return to their original communities, or remain refugees. This flow between different designations of mobile population can complicate the appreciation of the specific health and medical needs of vulnerable refugee populations and also affect the programs and policies intended to address and manage those needs. This paper will approach the health and medical needs of refugees and displaced persons from a holistic, process-driven as opposed to classification-driven perspective. It will be suggested that considering the health needs of refugees and displaced persons in this manner can more effectively manage some of the longer-term health challenges related to these vulnerable mobile populations.

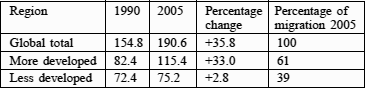

Table I - International migrants 1990-2005 (millions)

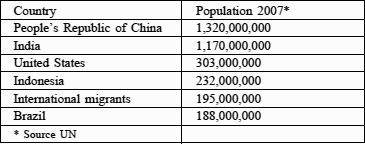

Recently, in combination with other globalization processes, the volume and scope of migration have been increasing, with the largest growth in mobile populations being observed in the developed world. In 2006 the UN estimated that the number of migrants in developed nations increased by some 33 million people between 1990 and 2005. The numbers of international migrants are significant and when considered in context the size of this component of the global population can be dramatic. If international migrants were considered a nation by themselves they would represent the world’s sixth largest country (Table II).

Table II - Population by nation including international migrants

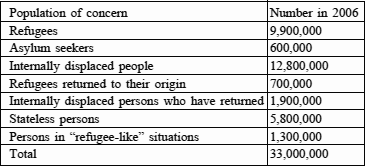

Table III - Populations of concern to UNHCR

The demographics and definitions of refugees and displaced persons

The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that there are some 33 million people who are of concern to that organization. That total includes seven different populations.

The definitions and descriptions for each of these populations are different although several of the groups share some characteristics.

Depending on location, situation, and the experience of those involved in dealing the populations each of these groups may be referred to as “refugees” or “migrants”. This lack of precision in description can complicate the appreciation of studies and investigations into the health needs of migrants and can make the cross-comparability of international studies difficult. To reduce the influences generated by the administrative and legal classifications of the various groups of migrants and refugees, and to make the appreciation of the health needs of mobile populations easier, it may be useful to consider health in the context of the migratory process itself.

Global factors that affect migrant health disparity

The health effects of migration fundamentally result from the interface of two components: mobility and disparity. If populations did not move between regions, differences in health characteristics and outcomes would remain localized issues of national importance only. Alternatively, if global health characteristics were similar, extensive travel and migration between regions would be associated with minimal health consequences. However, neither of these situations exists. International travel and migration are growing as integral components of globalization. At the same time there continue to be marked differences in both the prevalence of disease and illness and in availability and access of health services between many global areas. As a consequence, the health implications of migration are increasingly important in both national and international context.

Health needs and vulnerability needs related to stages of the process

a) Pre-migration phase

The complex relationships between migration and health can be more easily appreciated if the process of population mobility is considered as a series of sequential stages representing phases of migration. Considering migration in this manner removes many of the confounding influences that may be introduced through overlapping or inconsistent terminology related to the legal and administrative aspects of immigration. In this context the health needs of migrants can be related to four discrete components of the migration dynamic.

The first is the pre-migration phase. Migrants reflect the epidemiology and the health environment of their place and environment of origin. When they leave they carry several health determinants from their origin with them. It is important to note that many of the factors that influence the health of migrants in the pre-movement phase are social determinants of health. Poverty, social exclusion, education, housing - these can all directly and indirectly affect the incidence and outcome of disease and illness. At the same time a search for a better life or improved livelihood often encourages migration by the disadvantaged.

In the pre-departure phase vulnerability to health risks is greatest in those subject to poverty, social exclusion, and the consequential increased exposure to health and disease risks. Many of these factors are also related to the social and political forces that support or create refugee and displaced populations. Some of these are environmental, as observed in populations living in situations of poor housing where exposure to infectious agents is more common. Examples include tuberculosis and other respiratory infections, food- and water-borne disease, and vector-borne infections such as malaria. Even important infections of global public health significance such as avian influenza are more common in the marginalized who share living accommodation in close proximity to animals.

Additionally, local conditions at the migrants’ origin have implications for non-infectious illnesses and chronic diseases. Poor and marginalized populations often lack access to and use of health care services, meaning that the stage and nature of disease and illness can be more advanced and less often treated than in wealthier or less socially isolated communities. The consequences in terms of health needs are that some migrant populations or communities originating from deprived backgrounds may depart with health conditions that are more severe and/or less well managed than other cohorts from more privileged backgrounds who may originate from the same location.

b) Movement phase

The second phase of the process of migration involves the period of movement from origin to destination. During this part of the migratory process some mobile populations may be subject to important journey-specific risks and factors that may affect their health. While many migrants make the journey without encountering risks to their health, for some vulnerable populations this is the most dangerous phase of the migratory process. The very young, the elderly, women and girls, and families with one parent are often at greater risk during the movement phase of migration.

It is also at this time that some groups are can be exposed to environmental situations that can affect health or increase the risk of disease. This is commonly observed in the displaced, who may be housed for extended periods of time in camp or other temporary residence situations. When this phase involves transit through or residence in areas of inclement climate, limited access to water, health care services or conflict, the health risks and subsequent health needs increase.

These types of movement-related risks most commonly involve refugees, displaced persons, and disadvantaged migrant populations such as trafficked or smuggled persons. It is in these populations that serious issues related to the morbidity and mortality of migration occur, including the majority of cases of trauma, torture and death. The movement phase of migration is also the component where those who are trafficked or smuggled or are attempting to gain access by irregular or unauthorized means are at great risk of accident, death, or violence.

c) Arrival and settlement phase

The third phase of the migration process is the arrival and settlement component that occurs when migrants arrive at their new destination. For some migrants, such as temporary workers, asylum seekers who will not be accepted as refugees, and illegal or irregular migrants, this phase will be temporary. For immigrants and those who are successful in their claims of asylum the settlement component is permanent and their new place of residence becomes their new home. The arrival and settlement phase is associated with a diverse set of health needs. Some are directly related to the need for diagnosis and treatment of diseases and illnesses that are more common in other areas of the world that may have been imported with migrants.

In situations where these illness and diseases are uncommonly encountered at the migrants’ destination the health needs of the newly arriving population may differ substantially from what the host health system normally is used to managing. It is in this phase of the migration process that the impact of global disease disparities often becomes apparent to migrant-receiving nations. Examples in this context often include tropical or imported diseases (e.g. malaria, Chagas’ disease, tuberculosis) and illnesses that have been eliminated or prevented in the developed regions of the world (vaccine-preventable diseases, post-infectious valvular cardiac disease, advanced or untreated illnesses). Not all health needs and concern are related to infectious diseases. While public health attention is often directed towards infections, migrants often have health issues related to non-infectious diseases and illnesses. These may be conditions that exist at the time of arrival or they may develop overtime at the migrants’ new home.

Other health needs that occur in the arrival and settlement phase of migration reflect the social and economic health determinants that are the direct result of the process. Migrants may experience many limits and obstructions that impede their ability to access and utilize health services at their new place of residence. In some jurisdictions unofficial, illegal, or unauthorized migrants may be statutorily prohibited from using state or national health services or obtaining health or medical insurance. In other situations, fear of legislative or judicial response may deter these migrants from seeking care. The net result can be the progression of disease and delay of treatment with more complicated, expensive, and greater risk to both the migrant and the host society.

Even when migrants have the right to access or utilize care, some may find the actual access and use of such services limited. Linguistic and/or cultural factors can significantly affect the access, use, and efficacy of health care services by minority or migrant populations. Many migrant and refugee populations have specific ethnic and cultural needs that need to be addressed as part of the comprehensive health services programmes at their new homes. When these health services include promotion and prevention components, where communication and comprehension are vital, there can be great needs in terms of cultural and linguistic competency.

d) Return phase

The fourth phase of the migration process is the return phase. While the return phase has always been a component of the existence of migrant or temporary workers, this phase has become more important of late due to global geopolitical and economic factors. Historically, migratory movements tended to be unidirectional and newly arrived migrants were unlikely to return to their place of origin. The cost and time of travel often prevented migrants from undertaking return visits. Additionally, in the case of refugees and those fleeing for political reasons, there were often legal or civil barriers to their return. During the past two decades many of those impediments have diminished. Return travel is now less costly and more easily available and many of the civil and political barriers to the return of refugees and displaced individuals have vanished. Returned refugees and IDPs now account for increased populations of concern to international agencies. Return travel generates specific health needs as it can successively re-expose migrants to risks present at their origin. Additionally it has direct implications for the health of children born to migrants at their new destination who may return with their parents and family to visit friends and relatives at their historic place of origin. This particular type of travel, known as VFR travel (Visiting Friends and Relatives), is of increasing interest to the travel medicine and public health sectors.

Meeting the needs of the mobile

In order to adequately meet the needs of refugees and displaced populations it is necessary to understand the issues in context. For those not familiar with mobile populations the terminology can be confusing and lack of precision regarding the use of terms can make the comparison of international studies even more complicated. While the importance of administrative and legal classifications can be significant, several of those factors are location- or time-specific and may not lend themselves to ongoing global or regional programme planning and delivery.

Reducing those limitations in considering the health needs of migrants and refugees can be accomplished by attention to the following:

1. Attention to the persons themselves not simply to their immigration status

The health status and health needs of migrants represent the consequence of several geographic, social and biological factors and are not simply the product of the migrants’ legal status, foreign birth, or place of origin. As described above, two migrants originating from location and resettling at the same destination may have markedly different health risks and characteristics. Refugees, illegal and irregular migrants, those forcibly displaced, trafficked migrants, the marginalized, and the poor will commonly be at greater risk of adverse health outcome than the wealthier, who emigrate through regular processes. While both communities are often considered “migrants” or “immigrants” for the purposes of epidemiological reporting or health services planning - in fact they represent separate populations in terms of health parameters and needs. Similar situations occur when refugees are resettled. The granting of residence status following resettlement may confer the status of “immigrant “but their “refugee” history may have been associated with important health influences that are much different from those of other immigrants, even those originating from the same location.

Additionally, even though individuals and communities may have share the same legal status as “refugees”, they may have been exposed to markedly different health risks and influences. The social and economic health determinants related to their life before they became refugees can have fundamental influence on their health outcomes as refugees or displaced populations.

Particular populations of migrants are at greater risk for certain adverse health outcomes. Women and girls and families headed by single parents are often vulnerable during the movement phase of the migratory process. This vulnerability extends to the arrival period, when they may lack the community support and protection that supported them in their original home.

Addressing the needs of these populations requires focus on the actual history and background of the migrant community, not simply their administrative status or birth location.

2. Understanding the process

As the issues and implications of health in migrant and mobile populations assume greater regional and international importance, investigations, studies and reports on the health of migrants are becoming numerous. As the nature and process of migration have evolved considerably during the past three decades, effective understanding and comparing of the results and implications of this research requires current knowledge of the nature and process of migration. Migration health literature is often complicated by the frequent lack of precision in the use of terms and definitions. Terms such as “immigrant”, “refugee” and “migrant” can have regional or national meanings that may differ from the use of the same term in other locations. These can be very important distinctions when there are location-specific differences in whether or not certain migrant populations have access to health care, medical insurance, drug benefits, or other services. This has important implications in the international context involving refugees and internally displaced migrant populations (IDPs). The former, who most commonly have crossed international boundaries, can access international assistance and support through UN and other international organizations. IDPs, on the other hand, because they remain in their country of origin may not be able to access international support even though their needs may be as great as those of refugees. Appreciating the implications of the health needs of migrants requires knowledge and awareness of the processes and nature of migration in the modern international context.

3. Relating the process of mobility to specific health risks

As described above, treating migration and population mobility as a series of linked processes allows for a systematic, integrated approach to both assessing and addressing the health needs of the populations at risk. Vulnerability and exposure to particular health risks vary with the phase of the process. Some are discreet and may be effectively dealt with through one single intervention, such as the screening for management of imported infections at the arrival phase. Others are chronic, and while they may have originated during a particular component of the migratory journey, such as observed with torture and refugee populations, the health and medical sequelae require sustained and integrated response. Using torture as an example, those dealing with potential victims will need to be aware of the risks and have access to culturally appropriate screening and diagnostic interventions in order to identify victims and specialist referral systems to manage the consequences. For issues like violence and trauma the needs of the affected can extend well beyond the initial arrival period and may be lifelong.

4. Tailoring the response

Building on the principles outlined above, it is apparent that meeting the diverse health and medical needs of migrants in an effective and efficient manner will not be accomplished through a “one size fits all” approach. There are basic principles, related to the phases of the migratory process, that can be applied across the spectrum of international migrants. Using those principles in combination with an understanding of the specific population-based needs can result in the development and delivery of appropriate policies and programmes to address the diverse health needs of migrants and refugees.

Those programmes must include specific components that reflect specific aspects of migration and almost always need to involve several social, governmental, and community sectors. They must also contain sufficient longitudinal capacity to support continuity of care across the components of the population mobility paradigm. Individuals may present for initial care as asylum seekers or bona fide refugees and later become permanent residents or immigrants. Their health and medical future however, will continue to reflect their personal journey and not simply their administrative immigration or residency status. Some of the long-term health effects of refugee and refugee-like situations, particularly psycho-social conditions, may continue or present years after the experience. Meeting those demands requires an integrated health system designed to reflect the needs of the particular populations independent of their immigration status. Providers dealing with migrant and mobile communities need to understand the history and nature of the migration and refugee process and have access to tools that can facilitate care provision to these populations.

Lessons and best practices developed from migrant health delivery programmes indicate that to be effective, migrants must have unfettered access to services with minimal legal or administrative impediment. One of the cornerstones of programme delivery is the integration of cultural and linguistic competency in the planning for and delivery of medical services. It has also been demonstrated that health programmes directed towards migrants are more effective when migrant communities themselves are involved in programme planning and delivery. The recruitment of staff and providers from migrant populations improves service delivery.

Finally, the diversity of migrant populations and the ongoing evolution of migration itself continually change both needs and the demographics of the affected populations. Programmes that have been designed for a particular population, at a particular time, e.g. refugees from Darfur, may not be applicable inother locations or migrant groups. As a consequence ongoing review of migrant-centred health programmes is required and outcome based evaluation is required to demonstrate continued effectiveness.